From Skateboards to Spaceships: Gall’s Law in Design

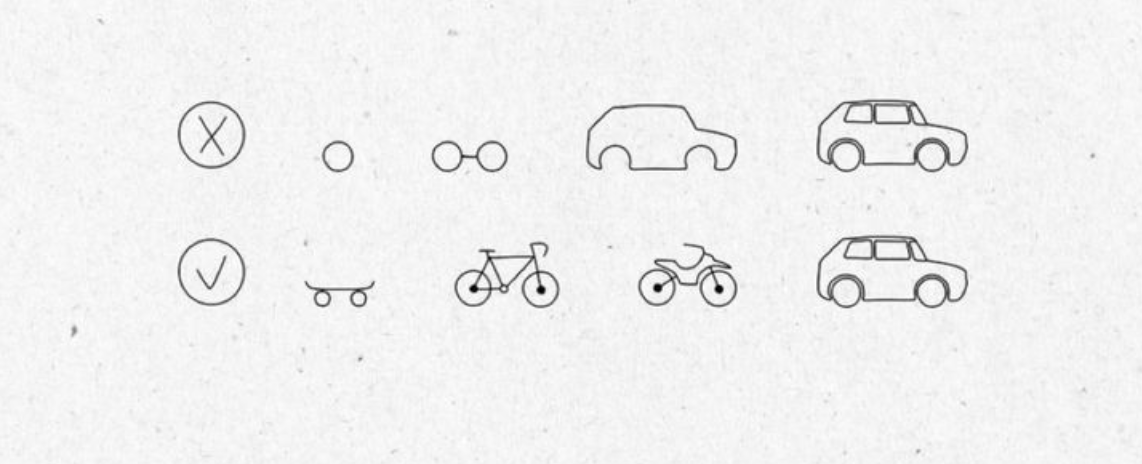

Great design rarely begins with complexity. The most powerful systems and products we use today originated as simple yet effective versions that focused on doing one thing exceptionally well. Growth begins when clarity is used to create a product that meets a real need and proves its value.

Complexity should emerge naturally, shaped by use, feedback, and evolving context, not by assumption or ambition alone. Designers who build with this mindset focus less on launching a grand vision all at once and more on creating something real and usable from day one.

In a world obsessed with scale, the most meaningful progress still begins with something small that works.

Gall's Law, introduced by systems thinker John Gall in 1975, gives a clear and powerful message to designers. It states that any complicated and reliable system almost always evolves from a much simpler one that has already worked well. Once you understand this, you begin to see it everywhere.

- The first version of the iPhone didn't have copy and paste or an app store. But its clean, focused design proved the idea of multi-touch before Apple started adding more features.

- The early version of Spotify only had one function: it streamed music legally and smoothly. Only after that basic experience proved successful over millions of hours did features like playlists, Discover Weekly, and podcasts get added.

- NASA's Apollo guidance computer also originated as a simple navigation device, initially tested on missiles. More complex features were added later, but only after the simpler version had already proven it could work in flight.

The strength of Gall's Law comes from two connected ideas:

- Growth through evolution

Evolutionary growth means that complexity is not added all at once; instead, it is gradually developed over time. It slowly builds around a working core, much like layers forming around a solid base. - Learning through feedback.

Feedback makes sure each new layer is functional by testing it in real-world situations.

Today's popular product design methods, like Eric Ries's Build-Measure-Learn loop, Jeff Patton's story mapping, and the Lean UX canvas, all follow this idea. They advise teams first to create a simple version that can handle a critical task from start to finish, test it with real users, and let real feedback, rather than guesses, shape the next steps.

Some people criticise Gall's Law, calling it overly simple. They argue that in certain fields, such as medical devices, air traffic control systems, or nuclear safety technology, the product must be complete and fully reliable from the very beginning. Rules and regulations can also make it hard to follow Gall's Law. For example, a peer-to-peer payment app must include robust security and identity checks from the outset, or it risks legal trouble.

However, even in these strict situations, the idea behind Gall's Law can still be helpful. Boeing, for instance, tested the flight control software for its 777 planes using a ground-based simulation rig called the "Iron Bird." This system simulated every part of the plane before it ever flew. In cases where testing in the real world isn't possible, testing in simulation can help build confidence in a simple version first.

Gall's Law can also fail when teams mistake "simple" for "incomplete." If a ride-sharing app launches without a map or estimated time of arrival, users are left confused, looking at a blank screen. That's not a functioning system but rather an unfinished idea. Design expert Donald Norman reminds us that good design should always clearly and completely deliver the most important task. A system should help users reach their main goal first. Simplicity doesn't mean cutting corners. It means focusing clearly on the most important outcome.

For designers who want to use Gall's Law practically, the best starting point is to write a clear and small story where a user's goal is successfully met. Jared Spool refers to this as the moment when a user's intention becomes visible in the product. Protect that moment from being crowded by too many features until you start seeing real data from users.

A useful tool here is the MoSCoW method, which categorises ideas into must-have, should-have, could-have, and won't-have categories. The MoSCoW Method is a simple yet powerful prioritisation framework that helps teams focus on what truly matters when planning features, requirements, or tasks, especially in design and product development. It breaks down everything into four clear categories based on necessity and impact:

M – Must Have

These are non-negotiable requirements. Without them, the product or project won't function or be viable. For example, in a digital wallet app, the ability to send and receive money would be a "Must-have."

S – Should Have

Important, but not critical. These features add significant value, but the system can function without them in the short term. Maybe your app "should" allow splitting bills or adding notes to a transaction—useful, but not blockers.

C – Could Have

Nice-to-have features that enhance the experience but are not essential. They are usually the first to be dropped if time or resources run short. Think animated transitions, dark mode, or minor personalisation elements. They add polish, not core value.

W – Won't Have (for now)

These are consciously excluded from the current scope. Not every idea needs to be acted on right away. This category creates clarity and focus, especially in design sprints. It doesn't mean "never," just "not now."

At the very core, Gall's Law teaches humility. It reminds us that no team, no matter how talented, can fully predict how a living, growing system will behave.

Instagram was first imagined as a way to share locations, not photos. However, after its launch, users began to focus on photos, which then became the heart of the app. Figma started as a browser-based graphic editor. Only later did real-time collaboration, initially a small experiment, become its most powerful feature.

Complexity, in this light, is not something you start with. It is something you earn. It grows by releasing something valuable and straightforward, watching how people use it, and making adjustments. Today, many startups dream big and pitch giant "platforms" before they've built anything. Gall's Law pulls us back to reality. It tells us to walk before we run.

Any system that is going to scale must first work in a smaller, simpler form. So, if your design plan feels like a giant blueprint drawn by someone who's never built anything, pause. Start with the skateboard version and test it. If it moves smoothly, you'll know how to add the next part. And if it wobbles, you'll be glad you didn't jump ahead to the whole car.

Member discussion