Lessons From London Immersion Program: What Great Designers Do Differently

I had an opportunity to attend the London Design Festival as part of the Extended Pack Collective's immersion program last year. Through the program, I had the chance to meet many designers and leaders across London. I also visited many design studios and organisations, which sparked a wealth of inspiration and learning.

Here is a blog documenting some of my findings and insights I would like to share with the design community.

Ten days in London

Studio visits at DixonBaxi, Conjure, and ustwo, designing everything from F1 graphics and Roblox worlds to McLaren HMIs and oil-rig controllers.

Days at the V&A. Nights in rooms where ex–Steve Jobs collaborators sat next to and L’Oréal design leads

Different disciplines, different scales, different approaches. But the designers who captivated me all had something in common. I listened intently to every word they said, making notes on each valuable insight gained from the battle-hardened skills they'd developed over the years.

I started asking myself: how can I become more like them, enigmatic, captivating, masters at their craft?

It's been nearly 160 days since I returned from London. As I've soaked in everything and applied it to my daily practice, I keep coming back to a few moments—instances that made me stop to think, that made me wonder what these designers were doing differently.

In today's article, I'll reflect on these moments and capture what I've noticed that sets good designers apart from great ones.

A panel of designers talking about their work and their role in designing things that would last over generations.

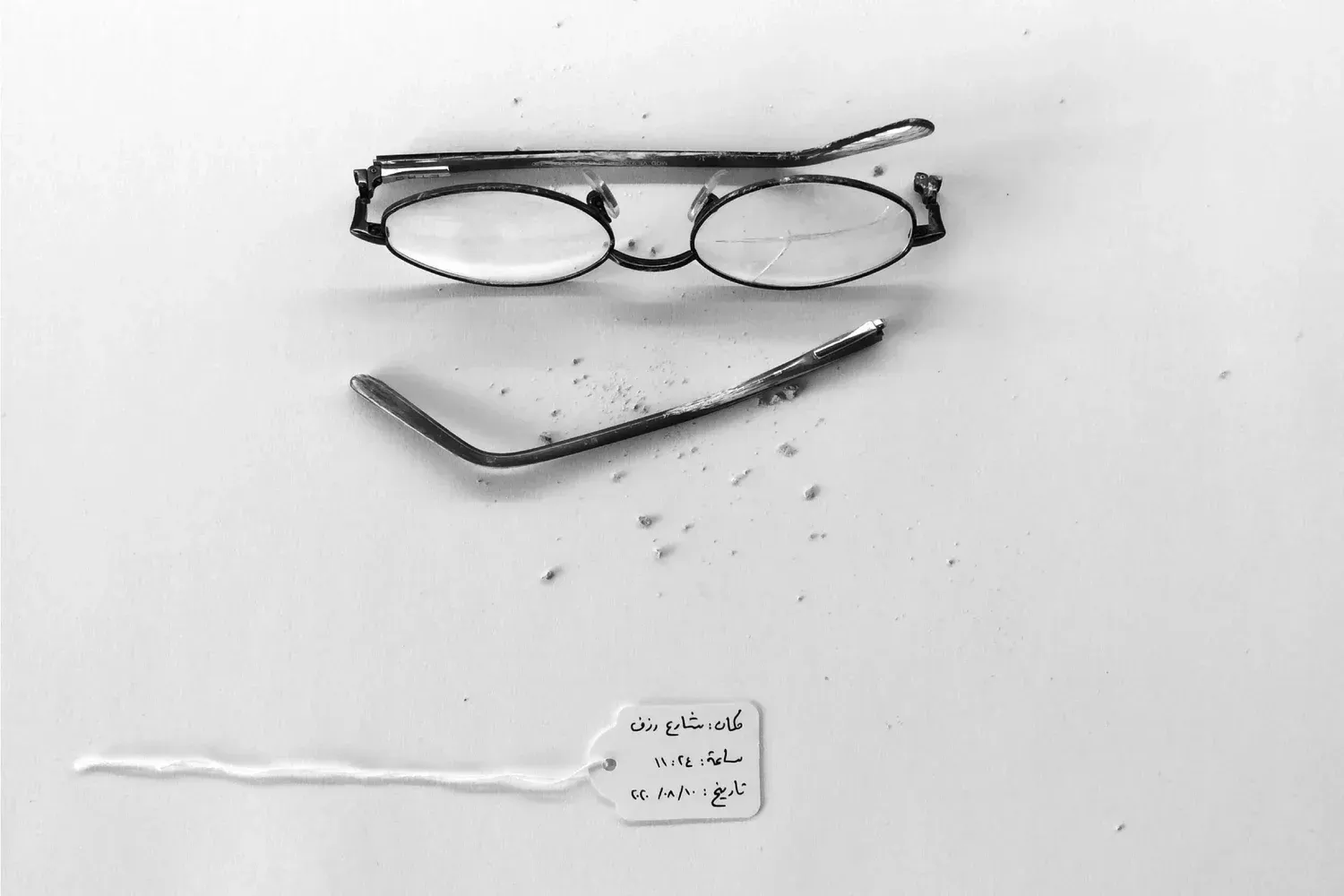

One designer and artist, Rana Haddad, spoke about an art piece she'd created as a tribute to a fatal accident that happened in her home country of Lebanon—the 2020 Beirut explosion, an explosion that resulted in at least 218 fatalities, 7,000 injuries, and approximately 300,000 displaced individuals.

As she described it, she didn't just show us the final work. She took us through a journey—why they were creating it, who they had in mind while making it, and the nuances in every decision.

Then she said something that gave me chills.

The art piece was laid on the ground rather than hung on a wall.

That meant people would have to bend down to look at it, to inspect it closely. The reason was simple but profound: she wanted viewers to bow down, to pay their respects through the act of viewing.

That kind of intentionality, that care for the human experience, was what made her captivating.

I noticed this across the other designers on the panel, too. Whatever they created carried a human touch. It stirred emotion. It was evocative.

They weren't just making things—they were creating experiences that meant something.

I was here to understand the designers who made great work, and what I was seeing was that great designers were great storytellers.

01: They tell stories, not just make things

That moment at the V&A stayed with me throughout the trip.

Rana Haddad wasn't just explaining her work about the 2020 Beirut explosion. She was making us feel why it mattered. She built empathy. She connected her decisions to human experience.

Great designers are great storytellers.

Not in the marketing sense, not spinning narratives to sell things. But in the sense that they understand their work exists in relationship to people. They think about how someone will encounter what they've made. What they'll feel. What it will it mean to them.

I saw this pattern again and again in London. The designers who captivated me could articulate not just what they made, but why it mattered and who. They made decisions with intention and could explain that intention in ways that resonated emotionally.

When Rana Haddad chose to place her art piece on the ground, she was telling a story about respect, about humility, about paying attention. The choice wasn't arbitrary; it was deeply considered.

Later that week, I was walking through the Design Museum, looking at an exhibit on the history of technology.

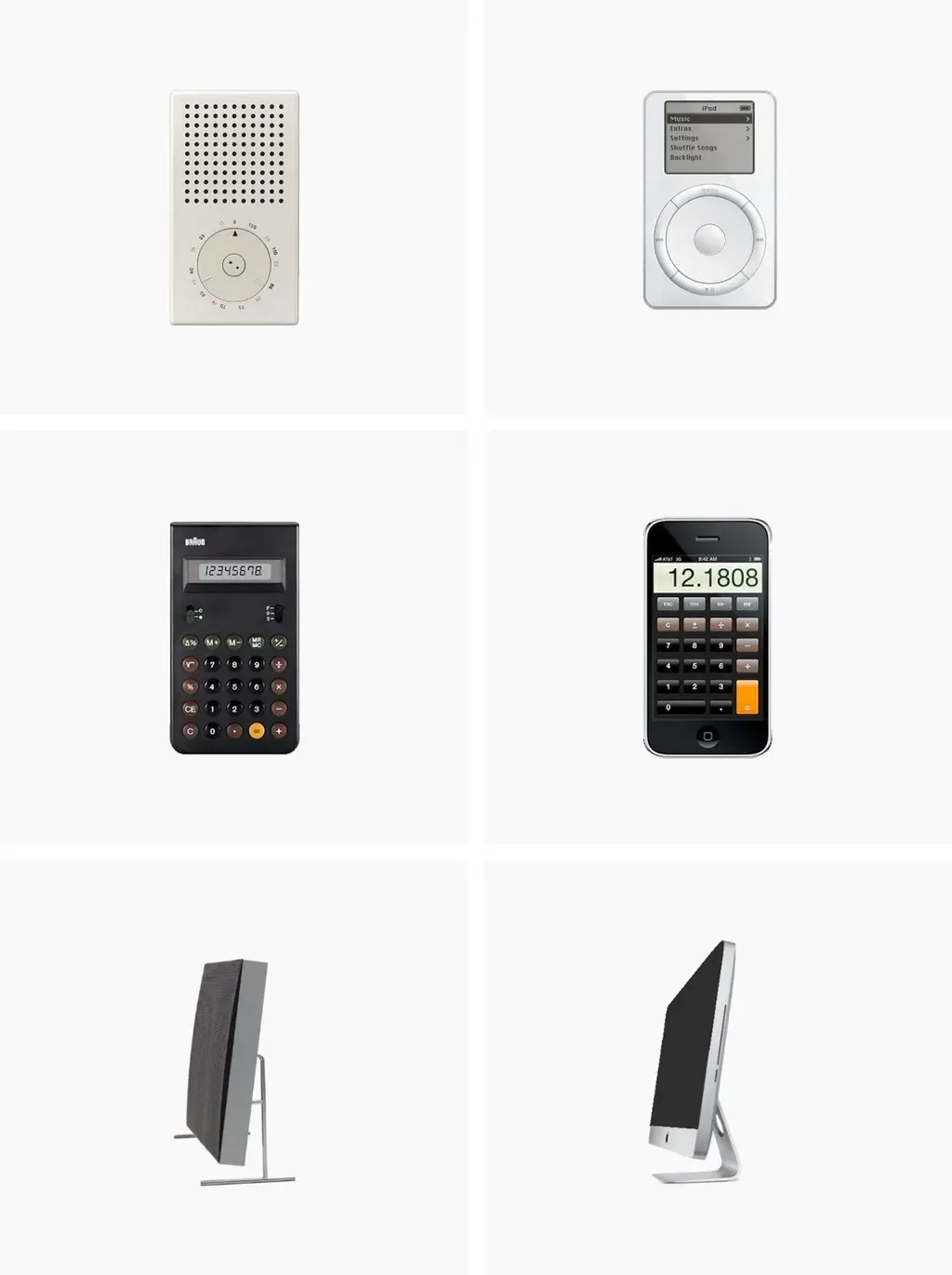

Braun radios from the '70s next to Sony Walkmans from the '80s next to early iPods. Some objects looked dated, trapped in their era. Others still felt modern.

As I was taking my time looking and absorbing this exhibit, something really interesting occurred to me - Here I would encourage you to pause and take a look at this Braun signal radio designed by Dieter Rams in 1978.

Braun products could sit in my bedroom today and still fit right in - they look relevant and modern despite being 50 years old since their inception.

What were Dieter Rams and his team doing that made their work feel so different? What mindset, what practice, what approach allowed them to create things that still resonated decades later?

02: They know what to leave out

I love technology, so I slowed down at the museum exhibit. Let myself take it all in.

Braun, Sony, and Apple. All solving similar problems—how to listen to music, how to tell time, how to interact with information. But the work felt fundamentally different.

I kept thinking about Dieter Rams looking at a radio prototype. What did he see that others didn't? What made him say "no" to the decorative elements everyone else was adding?

The Braun products had this quality: they looked the way they did because of how they worked. Clean lines because complexity was removed. Simple colours because they don't distract. Every button is placed where your hand expects it.

The designers had practised restraint.

Not restraint as "holding back." Restraint is knowing exactly what the work needs and having the confidence to stop there. Nothing more than needed, nothing less.

That's the practice. Knowing what to leave out requires a deep understanding of what matters. You can't remove the wrong things unless you know what the right things are.

The Sony and Apple products on that wall took bolder visual bets—shapes and colours that felt exciting in their moment. That expressiveness made people love them. But it also dated them.

There's a tension here. Restraint can feel less personal, less human. Expression can feel more temporary.

Braun’s products strictly adhered to the principle of the form following the function, rendering them modern even today.

This restraint soon would become a source of a great deal of inspiration for some of the most iconic products during the Jony Ive era of Apple.

The same era that gave birth to some of the most iconic products of modern times.

It showed me firsthand that great designers develop taste through subtraction. They play with ideas long enough to know what can be removed without losing the soul of the work.

The studio visits came next—first DixonBaxi, then Brinkworth a few days later, then ustwo after that.

I'd been to agencies and tech offices before, but walking into DixonBaxi, ustwo and Brinkworth felt different. It wasn't what I expected. No pristine minimalism. No "clean desk policy."

It was a controlled chaos.

03: Designing conditions for good work

These spaces weren't optimised for productivity in the traditional sense, but optimised for creativity.

Books on philosophy sat next to product catalogues. DJ decks in the corner. Objects with no clear purpose other than that someone loved them. Sketches pinned to walls. Experiments half-finished on tables. Music playing from a shared playlist the team curated together.

The spaces had personality. It felt like the designers there had given themselves permission to be messy, to try things, to leave evidence of their thinking visible.

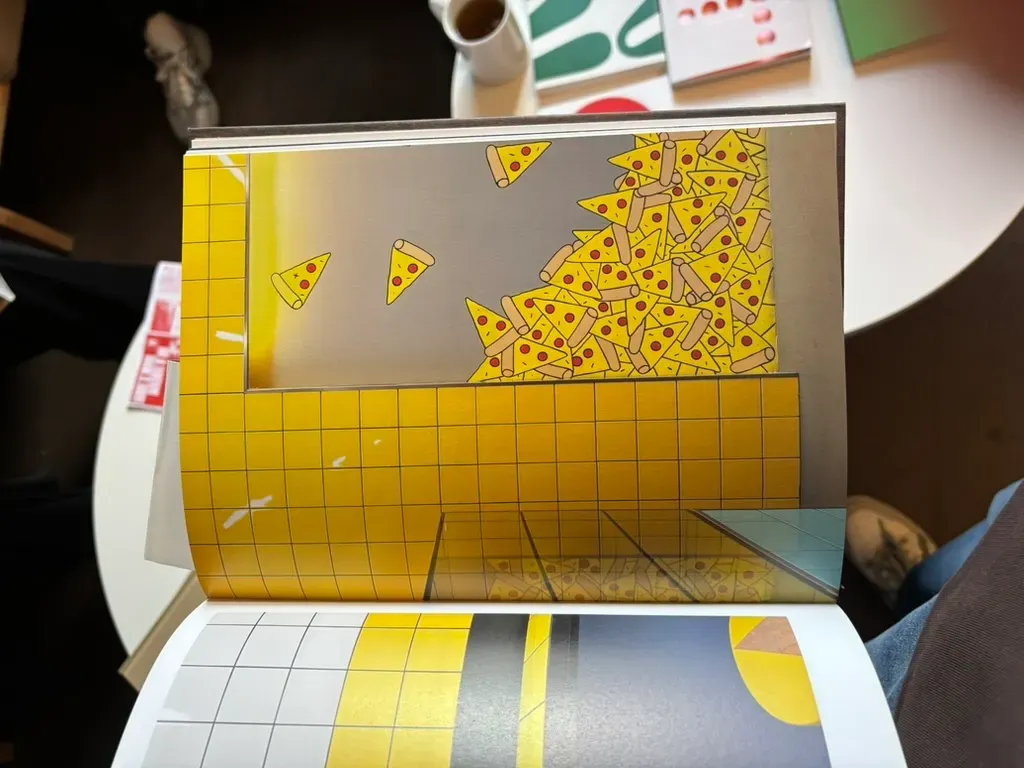

Another such detail kept appearing: books of their own work, displayed like trophies.

As a designer working on the digital medium, this really stuck out to me. Digital work is frictionless: easy to change, easier to lose.

When your day job lives on screens which are endlessly iterable and easily lost in folders and Figma files. It's easy to rely on endless iteration because nothing feels final.

But a printed book forces a decision. It says: this version mattered enough to finish. To hold. To show people.

Every studio had books of their own projects displayed—not digital portfolios on screens, but actual printed books you could hold.

The studios I visited weren't accidents. They were deliberately built to encourage play, risk, personality, and commitment.

Great design is made in environments that pull great work out of themselves and their teams. Creativity isn't just about talent—it's about creating the right conditions.

Look at your workspace. Does it encourage you to explore? Or does it pressure you to have answers immediately?

You can't think your way to great work. You have to make your way there.

A company that I believe truly understands this concept is Nothing. They make mobiles that defy modern-day rules for success in the extremely competitive and ruthless world of consumer technology.

It so happens that I had the opportunity to meet Hunnaid Nagaria, a creative technologist at Nothing.

We talked about many things, from his experience in designing the Nothing Ear 3 to his take on what makes good design. He mentioned something interesting about how many senior people at the company have strong musical backgrounds.

After this, I couldn’t unsee the inspiration that their products took from this musical world, all the way from the Glyph matrix to the unique synth ringtones.

04: The importance of creation in building taste

The music did not directly teach novel product design, but it shaped the taste of the designers behind the products, and it shaped how they applied those patterns to their work.

These weren't distractions. They were creative outlets that gave them joy.

It was permission to create for the sake of creating. We're so conditioned to optimise everything, even our downtime needs to have ROI. But hobbies aren't professional development in disguise.

They're permission to think differently.

- Music trains you to hear rhythm.

- Coding teaches you to see systems.

- Writing forces you to find structure.

But these skills transfer in unexpected ways. New patterns to recognise, new questions to ask, new ways to get unstuck when your usual approaches fail.

It’s important to create for the sake of creating - not for the views, not for the likes, but for the fun of it. It doesn't need to be design-adjacent. It just needs to be something you care about enough to keep doing even when it's hard.

Hobbies are not stealing time from your craft—they're feeding it.

You can't think your way to great taste. You have to make your way there.

Across ten days—workshops, studio visits, conversations with designers working in furniture, retail spaces, digital products, industrial design—one word kept coming up: play.

Not play as "fun and games." Play is a disciplined method for discovering what works.

05: Play more

Good work takes time to become clear. An idea starts messy. You pull it, test it, twist it, break it, try again. The real shape shows up only after you experiment.

We pressure ourselves to find the right answer immediately. But the designers I admired most had learned to trust the process. They knew that premature certainty kills interesting work.

What play looks like in practice:

- Try something quickly

- Get feedback

- Learn from what fails

- Move on

- Repeat

I used to despise the phrase "fail fast" because it sounded like an excuse for sloppy work. But the designers in London showed me something different. They weren't failing fast. They were learning fast. There's a difference.

Failing fast can mean being careless. Learning fast means being curious. It means treating every attempt as information, not as a verdict on your ability.

When you explore those dead ends, you don't just stumble on the solution. You gain unshakeable clarity on why the final path is the only way forward.

One sixty days later, I think I have an answer to the question I kept asking in London: What were they doing differently?

The designers who captivated me were the ones who seemed enigmatic and masterful and weren't following a formula. They were following a practice:

- They told stories, not just made things.

- They knew what to leave out.

- They designed conditions for good work.

- They had taste

- They took play seriously.

As people, they were perceptive, articulate, evocative and deeply empathetic.

But most importantly

They were excited. They were present. They cared deeply about what they made and how they made it. And that care was contagious.

Not just skill or knowledge, but genuine engagement with the craft—and genuine care for the people who will experience what you make.

This trip marked a transformative change in my outlook on what it means to design and build great things. I left London wanting to make work that feels human. Timeless. Iconic.

Now, when I see something interesting and unique? I buy it. It's an investment in taste.

I'm printing my work in books now. Making it tangible. Making it real.

And honestly? I feel more in tune with my work every day. More confident in my judgment. This article is me trying to pass that feeling to you.

Here's what else I didn't expect:

Finding my people.

Outside the talks and events, I realised - you need your gang. People who echo your passion. Who push you to do better because they actually care.

That's not optional. That's essential.

So if you made it this far:

Take this as your sign.

Stay excited. Keep questioning. Play more.

Build your practice. Find your people. Make things that matter.

Find me on LinkedIn - feel free to reach out, I am always down to chat.

Member discussion